"The Maneuver", by William Carlos Williams. From his Collected Poems (and bravo to New Directions for allowing Google Books to allow multipage previews when you search it!)

Sunday, July 29, 2007

Sabbath Poem - The Maneuver

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

7/29/2007

0

comments

![]()

Labels: birds, poetry, sabbath poems, voice, william carlos williams

Saturday, July 28, 2007

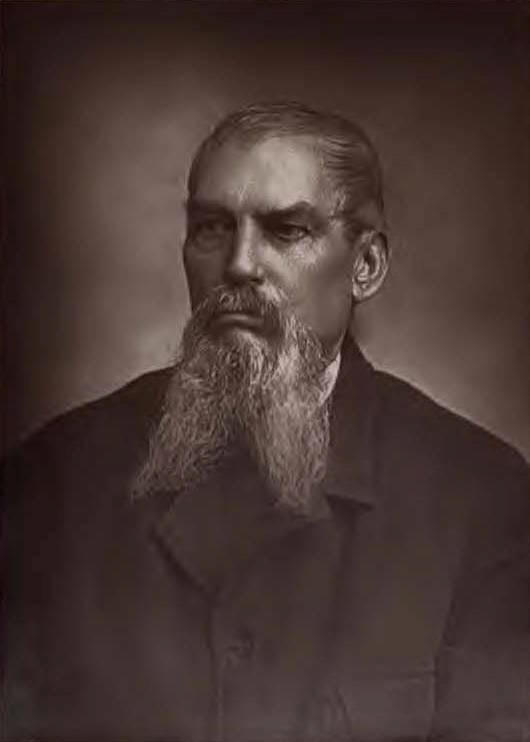

Letters from the Battle-Fields of Paraguay

This week I finished reading Richard F. Burton's Letters from the Battle-Fields of Paraguay, a narrative of travels the famed Victorian explorer-linguist-diplomat undertook during the closing phases of the disastrous (but attractively-named) War of the Triple Alliance, at the turn of the 1870s. Burton's journey was a sort of offshoot as his tenure as a British consul to the Brazilian Empire, and it's clear that, as far as the war went, his sympathies were with the Brazilians (and to a lesser extent their Argentine and Uruguayan allies). Like most old travel writing, it refuses to resonate for long with modern interests (hence: his true-to-title detailed descriptions of mouldering earthworks, artillery positions and peculiarities, written for an age familiar, after the Napoleonic, Crimean and US Civil wars, with the terminology), and ruffle modern feathers (of course he says all sorts of insensitive, scornful things about the people and cultures he encounters—though with Burton, it's scorn backed up, right or wrong, by brilliance and deep and broad linguistic and cultural knowledge: twenty-odd languages mastered; as many countries and colonies on four continents explored).

This week I finished reading Richard F. Burton's Letters from the Battle-Fields of Paraguay, a narrative of travels the famed Victorian explorer-linguist-diplomat undertook during the closing phases of the disastrous (but attractively-named) War of the Triple Alliance, at the turn of the 1870s. Burton's journey was a sort of offshoot as his tenure as a British consul to the Brazilian Empire, and it's clear that, as far as the war went, his sympathies were with the Brazilians (and to a lesser extent their Argentine and Uruguayan allies). Like most old travel writing, it refuses to resonate for long with modern interests (hence: his true-to-title detailed descriptions of mouldering earthworks, artillery positions and peculiarities, written for an age familiar, after the Napoleonic, Crimean and US Civil wars, with the terminology), and ruffle modern feathers (of course he says all sorts of insensitive, scornful things about the people and cultures he encounters—though with Burton, it's scorn backed up, right or wrong, by brilliance and deep and broad linguistic and cultural knowledge: twenty-odd languages mastered; as many countries and colonies on four continents explored).

Still there's much of interest to quote—mostly with a wincing sort of humor. So I'll get on with it, in order of appearence in the book. First, some proof of Burton's general view that Paraguay had it (i.e. near-total destruction at the hands of the Alliance) heartily coming:

The war in Paraguay, impartially viewed, is no less than the doom of a race which is to be relieved from a self- chosen tyranny by becoming chair a canon by the process of annihilation. It is the Nemesis of Faith; the death-throe of a policy bequeathed by Jesuitism to South America; it shows the flood of Time surging over a relic of old world semi-barbarism, a palaeozoic humanity. Nor is the semi-barbaric race itself without an especial interest of its own. The Guarani family appears to have had its especial habitat in Paraguay, and thence to have extended its dialects, from the Rio de la Plata to the roots of. the Andes, and even to the peoples of the Antilles. The language is now being killed out at the heart, the limbs are being slowly but surely lopped off, and another century will witness its extirpation. [link]Luckily the nation, civilization, and language did survive (see an earlier post for a bit more on that). For one so scornful, though, Burton did spend three years "mastering" Tupi-Guaraní, and throughout endeavors to search out proper etymologies for placenames (commenting that if he doesn't, he's sure they'll soon be lost).

And first of the word "Paraguay," which must not be pronounced "Paragay." The Guarani languages, like the Turkish and other so-called "Oriental" tongues, have little accent, and that little generally influences the last syllable : a native would articulate the name Pa-ra-gua-y. [link]Language done, he moves on to diet. Paraguayans, from what I hear, now eat tons of meat, just like their Southern Cone neighbors.

The Paraguayan is eminently a vegetarian, for beef is rare within this oxless land, and the Republic is no longer, as described by Dobrizhoffer, the "devouring grave as well as the seminary of cattle." He sickens under a meat diet; hence, to some extent, the terrible losses of the army in the field. Moreover, he holds with the Guacho [sic, Gaucho], that " Carnero no es came"—mutton is not meat. Living to him is cheap. [link]Burton is deeply anti-Jesuital (I wonder what he'd made of the movie The Mission? "Popish propaganda!") and blames the Paraguayans' so-called infiriority on the centuries-past influence of the priests.

A curious report, alluded to at the time by most Jesuitical and anti-Jesuit writers, and ill-temperedly noticed by Southey, spread far and wide—namely, that the Fathers were compelled to arouse their flocks somewhat before the working hours, and to insist upon their not preferring Morpheus to Venus, and thus neglecting the duty of begetting souls to be saved. I have found the tradition still lingering amongst the modern Paraguayans. [link]For all the scorn and asides, Burton does write beautifully and precisely, especially—to modern eyes—in numerous sections describing the natural vistas of the wide and mighty Paraná river. I've read quite a bit about Argentina but this enriched the picture like nothing else:

The channel winds wonderfully, to the east, to the south, and to the north-west. Rival channels abound, and we often see far beyond the monte-bush, to our right and left, ships' sails passing up over land like the sailing waggons of the Seres. When the waters are out, temporary cross-cuts, as on the great Rio de Sao Francisco, enable boats to cruise across country. The riverine edges wax higher as we advance, and whilst one side grows grass the other becomes tree-clad; higher up, this formation will assume larger and more distinct proportions. From this lower bed the larger animals, so common up stream, have of late been frightened away ; the fish to breed in the tributaries and the less disturbed parts ; and little life save aerial remains. At rare times a bullet head protruded from the water and at once withdrawn denotes the "Nutria" indifferently described as an otter, a seal, or a sea-wolf. The shag, plotus, or diwr, is of two kinds, one dingy brown, the other black with white-tipped wings and a plume that commends itself to what wears bonnets. They gaze at us with extended necks and " bob" down stream, in remarkable contrast with the hunchbacked, motionless Mirasol or white crane, standing one-legged and meditative on the bank, and with the Socoboi, the large ash-coloured heron, roaring like a bull because we dare to disturb him. [link]But, soon enough, back to scorn. Burton finishes with the boring paltry fortifications and arrives in Asuncion, the evacuated, occupied Paraguayan capital (the dictator Lopez having taken his soldiers into the jungle to fight to the end). That final sentence presages great bitter 20th century travel writers like Graham Greene, V.S. Naipaul and Paul Theroux:

A few paces beyond the cathedral lead us to the Hotel de la Minute. The house once belonged to a Paraguayan of importance. It fronts a new theatre of ambitious size, said to be built upon the model of " La Scala/' and fitted for 1000 spectators. Its flanks are one hundred yards long; in fact, it occupies a whole " cuadra."* The brick walls that back the three tiers of boxes are four feet thick; they must be fearless of fire, and, after the usual theatres of South America, they suggest the Coliseum. The building was unfinished, and of course a dead mule occupied the inside. [link]Finally he gets round to the weather:

It is popularly said here, as in the Brazil, that summer and winter meet in one day, and that Paraguay combines the four seasons in twenty-four hours. Between midnight and 6 A.M., it is spring; summer then extends to noon: the third quarter is autumn; and from 6 P.M. to midnight it is winter. [link]One closing note: Burton himself enjoys poking fun at the various names given to Paraguay by analogy-hungry writers of his era: "The China of South America" (both closed contries! both grow 'tea'!), "The Sebastopol of the South" (just like the Crimea! in that there was a war!), and—my favorite—"Prester John's Southern Kingdom" (a lost tribe of primitive, wealthy Christians!). And, clearly, so do I.

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

7/28/2007

0

comments

![]()

Labels: argentina, brazil, catholic, guarani, lost tribes, paraguay, south america, travel, uruguay, victorian

Thursday, July 26, 2007

High-End Architecture for the Poor: Solidarity or Slumming?

Simon Romero / NYTimes:

So on the one hand: what a cool idea! And how refreshing to hear about a leader working to bridge the gap between rich and poor by giving the latter some actual good, helpful services, and by honoring them with "the best" rather than "the adequate". The article does touch on a couple of critiques for such a scheme—wouldn't it be better to spend the money on improving basic services?, and um, do the folks in the neighborhood actually appreciate the "beauty" that their mayor's worked to bring to them? Sometimes high-concept architecture gets, um, tried out on the poor because it's easy for visionary city planners to push it through on them. I remember the first time I went to New York City, riding the train past all these massive housing project towers, and realizing it looked exactly like the early 20th century futurism I'd been reading about—Corbusier and his World's Fair knockoffs, "the home as a machine for living" etc. Back then the visionaries had said, "in the future we'll all live in these great planned housing complexes". So they built them first for the poor, to prove the concept. But in the end the rich never signed up for their own housing projects—so the only people who lived in the futuristic world were those who didn't have much choice.MEDELLÍN, Colombia, July 11 — Dressed in jeans and a T-shirt, sporting three days’ growth of beard and unruly hair nearly down to his shoulders, Sergio Fajardo looks every bit the nonconformist mathematician who spent years attaining a doctorate at the University of Wisconsin.

But that was a past life for Mr. Fajardo, this city’s mayor and the son of one of its most famous architects. Now he presses forward with an unconventional political philosophy that has turned swaths of Medellín into dust-choked construction sites.

“Our most beautiful buildings,” said Mr. Fajardo, 51, “must be in our poorest areas.”

With that simple idea, Mr. Fajardo hired renowned architects to design an assemblage of luxurious libraries and other public buildings in this city’s most desperate slums. [full article]

Back to Medillin—for a while I've been puzzling over why, when it comes to my Colombian news, I prefer the front page of the Medillin El Colombiano over the better-designed, more-nationally-focused, Bogotá-based El Tiempo. (I've linked the websites, but visit Newseum to see the latest front pages: El Colombiano; El Tiempo) I think maybe it's to do with the mix of big-city news and charming provinciality—the annual flower fair, or textile week. Plus lots of coverage of cycling and inline skating. But also, the article made me realize, quite a bit about public art (both high-concept sculpture and more populist Christmas lights on the aerial tramway). So perhaps the mayor's to thank for that. I hope his work appeals to the locals—from every background—even more than it does to me.

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

7/26/2007

0

comments

![]()

Labels: architecture, colombia, design, futurism, justice, leadership, newspapers, parochialism, populism, public works, south america

Monday, July 23, 2007

Dümmer in English?

Sign and Sight recently featured a translation of this Frankfurter Allegemeine-Zeitung op-ed, calling for an increase in German-language scientifc writing. Or rather, presumably, an end to its precipitous decline.

I've remained deeply fascinated by linguistic-nationalist-scientific-activism—old thesis topics die hard. Phrases like "new terminology must be coined!" always get me smiling (interestingly enough, I have an opposite reaction to those "there ought to be a word for" type features one finds in the back of magazines like The Atlantic, or in the innumerable Sniglets volumes of yore—they're always kind of annoying to me, in that they're all but totally unserious about their coinage—invariably a horrendous pun-monster—and, besides, there usually does exist a more or less elegant turn of phrase that would serve the purported purpose nicely). Right, but back to the article:

Anyone who only encounters scientific research in a foreign language pays a heavy price, even if he is a master of the idiom. "We are dumber in English" – this was the conclusion that researchers came to in Sweden and the Netherlands, where children were introduced to English on their first day of school. Lectures in English are part of every subject, but nevertheless, the test results are about ten percent lower on average than in courses taught in the mother tongue. In English seminars, students ask and answer fewer questions; they give the overall impression of being somewhat more helpless. Neither students nor teachers are generally aware of the problem, because they all overestimate their expertise in English.I'd love to track down the study—Google only returns references to the aforementioned article. The quote makes it sound like each student took some courses in English, and some in his or her native tongue. But was the division uniform (e.g. math in English, art in Swedish), or did some in the study do the reverse (English art, Swedish math) and show the same ten percent drop? Other permutations abound (teach in English, test in Swedish?).

But back to our op-ed's prescription:

It shouldn't hurt German scientific language if, in the course of everyday research, publications appear in English. Such articles almost always deal with tiny advances in knowledge – like the question of whether or not gene X is expressed under the influence of protein Y. They are oriented towards a small audience, they seldom influence scientific concepts and they are, even if composed by native speakers, usually linguistically as outstanding as a manual for a DVD player. [!!!–ed.]Ah, the big questions: what is science? What is German science? And how do we do it? Now leap to the end:

But a pile of puzzle pieces is still not science. Every discipline needs publications that show connections, transmit inspiring ideas and sketch out new concepts. Such work is intended for colleagues beyond the narrow realms of one's own field and broaden the circles of knowledge. They are nourished by their use of language, because the author wants to lead the public through a distant and foreign territory, and thus wishes to be as convincing as possible. In order to preserve German as the language of science [Um das Deutsche als Wissenschaftssprache zu erhalten], we should make an effort along these lines.

If we re-learn how to tell the story of science, then German will have a future as a language of science. [Nur wenn wir wieder lernen, Wissenschaft zu erzählen, hat Deutsch als Sprache der Wissenschaft eine Zukunft.]I'm interested in the translator's choice to say both "German as the language of science" and "German as a language of science". Whether intentionally or not, it does get at an ambiguity of the article's vision: does he think that, simply, everyone would benefit from learning and "doing" science in their mother-tongue, or that German is better-equipped (at least till all the German scientists utterly lose the ability) as language for the clear expression of scientific "big ideas"?

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

7/23/2007

0

comments

![]()

Labels: education, english, german, history of science, mother-tongues, nationalism, science, translation

Sunday, July 22, 2007

Sabbath Poem: Under One Small Star

"Under One Small Star", by Wislawa Szymborska. Translated from the Polish by Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh. (Here's the original: "Pod jedną gwiazdką")

Discovered, like so many of my new favorite poems, via Lawrence Weschler's wonderful, wide-ranging guest sessions on transom.org. Here's my reading:

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

7/22/2007

0

comments

![]()

Labels: apologetics, lawrence weschler, polish, sabbath poems, translation

Wednesday, July 18, 2007

Library Marginalia

This morning I started David Mitchell's novel Black Swan Green—seems quite promising, and it's come highly recommended. A few pages in, I found the following annotation, evidently added by a reader somewhat younger than Mitchell's 12–year–old narrator. I'm actually kind of a collecter of library-book marginalia, so I was rather pleased, and fired up the scanner. It reminded of some similar Kindergrafitti from German Art from Beckman to Richter. In the latter, a half-dozen spreads from the "about the artists" section had been annotated, the young Kunstkritik generally starting from the faces and working outwards.

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

7/18/2007

0

comments

![]()

Monday, July 16, 2007

Soccer Semaphore

Yesterday I took a (short) break from the Tour de France to watch the Copa America final, between Argentina and Brazil. Brazil won 3–0, though Argentina did at least manage to score once against themselves.

After the first Brazilian goal, I did a double-take at the crowd reaction shots: was that a Lebanese flag waving there? Rewind. Yep. I don't think the player had any connection with Lebanon (like the player from Ghana who celebrated his World Cup goal with an Israeli flag—he played professionally for a Tel Aviv club). More likely some Lebanese Brazilians up from São Paulo or even Foz do Iguaçu. Or maybe some Lebanese Venezuelans (since the final was, after all, in Maricaibo).

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

7/16/2007

0

comments

![]()

Sunday, July 15, 2007

Sabbath Poem: La Palabra

"La Palabra", by Pablo Neruda. [Spanish text w/translation] I first read this in a bilengual edition of Fully Empowered. The last couplet stuck with me in Spanish from the start, but only lately have I been feeling confident enough in my skill to try memorizing the whole thing in the original. At present I've got about three-quarters done (one recitation every morning for about a month). Maybe another week or two and I'll be there. In the mean time, here's what I sound like reading it. I seem to have adopted a quasi-Argentine way of pronouncing my y's and ll's, even though most of the Spanish I hear is of the Mexican-influenced Univision Newscaster Standard.

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

7/15/2007

0

comments

![]()

Labels: accents, neruda, newscasts, poetry, pronunciation, sabbath poems, spanish, voice

Saturday, July 14, 2007

The View from Above

Brou Monastery, Bourge-en-Bresse, France, which looks even better from a helicopter. [flickr source]

Watching the Tour de France this week, I'm amazed by the consistently great aerial camera-work that accompanies the broadcast—not only those entrancing shots of the peleton morphing and shimmying like a shoal of tropical fish—but the postcard views of the landscape along the way.

One thing that's amazed/interested me is how the most attractive buildings from the air are just about always those that were built before there was much chance of them being seen from the air (still more so if we discount ballooning). The ones built in the past century, though, are just about always uglier from above than from the ground. Blame flat roofs and air conditioners I guess. Maybe the ubiquity of Google Earth and other identifiable aerial views will inspire top-tier architects to give greater weight to the view from above. Or maybe they'll just rent it out as billboard space.

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

7/14/2007

0

comments

![]()

Thursday, July 12, 2007

The Ergonomics of Terror

Last week on one of the newscasts I watch (Univision? Les 20 Heures?), the jihadi-video-excerpt-o-the-day showed these three black-clad guys jumping around a corner and striking poses, almost Charlie's Angels style, but holding their Kalashnikovs sideways—a posture I'd seen only with handguns, and generally in a hip-hop sort of context ("a cooler but less accurate way of aiming").

It seemed to me that firing a machine gun held sideways would pose some ergonomic issues—would the 90 degree rotation increase the recoil stress on the wrist? I emailed a friend of Muslim background who, more importantly, spent a few years in the US Army. Here's a bit of his reply:

I have heard the AK kicks a bit, so they'd have to be pretty strong to hold it like that with one hand, not resting it on a shoulder and get bullets anywhere near the targets, so that makes me think they're just posing and not practicing.The bigger question I have is to what extent the guys who make these videos are purposely referencing American-style violence, and to what extent they've just assimilated it. (Are they familiar with hip-hop videos, for instance?) My friend doubted that theory: "I fully believe that they have just assimilated. If they thought about it at all, they would realize that copying American style violence is antithetical to the purpose of their violence."

As for cartridge release, that's probably the biggest problem for them. Being orthodox Muslims, they should be firing their rifles right handed. Almost all rifles are built for right handed people, so the spent cartridges shoot off to the right and to the back of the rifle. This pushes them back away from the person firing. If they were to the rifles sideways with their right hands, the cartridges would shoot up and back into their faces or down their shirts. Only a lefty would benefit from a sideways hold. I used to get hot cartridges in my shirt all the time. almost made me consider firing right handed. If I could get any kind of stability with a sideways grip, I'd probably have used it, but it was completely unstable with the M-16. Also, I would have been obliterated by a drill sergeant for trying to be cool.

Again, however, I don't know the AK.

Often when I see the excerpts of these videos I start wondering more about how they're made and directed, who provides the background music (sympathizers with synthesizers?), and so forth. But—as was the case when I tried briefly to track down the video that inspired this post—this is the sort of research that makes me queasy, or at least that I have mixed feelings about entering into just because it's "interesting" in a way abstracted from the life and death matters at hand.

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

7/12/2007

0

comments

![]()

Tuesday, July 10, 2007

Hocuspokus-Handy!

One day last year I was looking at a page from the Vienna newspaper Der Standard, and fixed on this "Hocuspokus-Handy" graphic. It took me a little while to make the Handy = mobile phone connection. I thought it might be an Austrianism—a friend studying in Berlin didn't seem to know about the term. Finally, this week, once more 'twas LanguageHat to the rescue:

One day last year I was looking at a page from the Vienna newspaper Der Standard, and fixed on this "Hocuspokus-Handy" graphic. It took me a little while to make the Handy = mobile phone connection. I thought it might be an Austrianism—a friend studying in Berlin didn't seem to know about the term. Finally, this week, once more 'twas LanguageHat to the rescue:

Anatol Stefanowitsch in Bremer Sprachblog discusses the question Woher kommt das Handy?: where does the German word Handy 'mobile telephone, cell(ular) phone' come from? After rejecting various theories (such as that it's short for the 1940s term handie-talkie), the floor is thrown open to suggestions, and Detlef Guertler of Wortistik linked to a post there proving to Anatol's satisfaction that it comes from a term for 'hand-held microphone' used in the CB radio community.A few years further back still, I remember a descent on Singapore Airlines in which were admonished to cease using handphones, which, with the Singaporean accent's elegant unreleased stops, I took for "headphones", which still seemed odd. But then next came the "Now would be a good time to try and flush your heroin down the toilet if you wish to avoid the death penalty" announcement (or words to that effect), so oddness was clearly relative.

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

7/10/2007

0

comments

![]()

Sunday, July 8, 2007

How Do You Say Yvyvy?

Sometimes following the news from Paraguay pays off. Yesterday I checked my newsreader and found the following headline, from ABC Digital:

Ante posible búsqueda de plata yvyguy en el Botánico, ediles suspenden obrasFrom what I can gather from the rest of the article, apparently digging for buried treasure is forbidden in the Botanical Gardens (but is tempting), and the approval process for this bathroom-construction (which might be a front for other searches?) is a bit sketchy.

En el Jardín Botánico se estaría realizando excavaciones en busca de tesoros escondidos según la sospecha de algunos concejales. Responsabilizan de las perforaciones a la Constructora Fortaleza, que en mayo suscribió un convenio con la Municipalidad de Asunción para la construcción de dos baños.

---

Authorities suspend excavation before possible search for yvyguy silver in Botanical Gardens.

Excavations have begun in the Botanical Gardens in search of hidden treasures, according to the suspicions of some councillers. The Constructora Fortaleza is responsible for these works, which were approved in May by the Munincipality of Asunción for the construction of two bathrooms. [my poor translation, of course]

Of course what really jumped out at me was the phrase plata yvyguy. It seems to be an accepted Spanish/Guaraní hybrid phrase. And, as best I can tell refers to treasure which was suppposedly hidden around the time the Jesuits were expelled from their missions in Paraguay in 1768. (The book of Guaraní legends I have devotes a page or two about a supposed lost tribe and treasure dating from the expulsion.) In any case, this particular sort of hybrid is pleasingly symbolic of what makes Paraguay so interesting: a relatively even mix of Spanish and Guaraní, pre- and post-colombian culture, and a deep sense of a richness that lies beneath, undiscovered (in the sense that Paraguay itself has been isolated by geography, by history, and by choice over the years).

But back to the word itself, the typo-looking yvyguy—what a lovely odd-looking string of letters! A few searches later, I turned up an anternate version, plata yvyvy, which was an even more pleasing row of letter-forms. I was reminded of certain pleasing Tanzanian placenames like Ujiji (you know, where Stanley met Livingstone), with all those cute little dots in a row.

But how to pronounce the forbidden plata yvyvy? Luckily my good friend Christine happens to be in Asunción right now, studying Guaraní and blogging about it from time to time. I emailed her with my guess at pronunciation: "ee-vee-vee", but was sadly corrected:

The y here is super hard to pronounce... it's a guttural vowel unlike any that we have in either English or Spanish. My guess is that to replicate it, one should imagine the sound one might make when punched in the gut.I tried that—lightly hitting my stomach while trying to get out a couple of v's—to much amusement but no avail. This Guaraní phonology offers more analogues (German ü, Russian y, French u) and detailed anatomical instructions ... but I still can't get it to mesh right with the v's.

I do now know that yvy means "earth", and -guy seems to be a suffix meaning "under", with the alternate -vy suffix meaning "half". That's a big maybe considering how little I know about the language, but "under-earth silver" seems a good guess for buried treasure.

Meanwhile, Christine ends her blog post on the subject with another amusing observation:

There's another guttural vowel, too. Well, nasal-guttural vowel. It's written as y with a tilde over it (looks like ñ but instead of having an n it's got a y). To the best of my listening ability, this sounds like the sound you hear, in Super Mario Bros II, when little Mario or Luigi (depending on whether you're the first player or second player) jump up into the air just at the moment when you hit the button. Is it the B button or the A? I can't remember... it's been a while since I last played.The tilde-y is actually available in (very rough) Unicode: Ỹ and ỹ. For some reason, though, they didn't wind up encoding a tilde-g, which is also used in the language, so I think people either type it as g~ or as ĝ with a neat little French hat.

Speaking of little hats in France: another good friend, recently back from Paris, emailed me about the odd Space-Invaders-style mosaic graffiti that he saw around town. Clicking through the photo gallery, I found, among the aliens, a little Super Mario by a brasserie. Vandalism seems much less offensive when it's done using more traditional artisanal methods.

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

7/08/2007

0

comments

![]()

Sabbath Poem: What We Need Is Here

I think I'll start a tradition of Sunday poetry recitations—largely from the sheaf of memory-poems I have clipped together hanging from a nail on my bedroom wall. I'll launch things, appropriately enough, with one of Wendell Berry's, "What We Need Is Here", from A Timbered Choir: The Sabbath Poems 1979–1997.

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

7/08/2007

0

comments

![]()

Labels: audio, poetry, sabbath poems

Tuesday, July 3, 2007

The Victoria Falls of South America

Yes, the title is ironic, but not in the way you might think.

To start, let's set the scene with some video, courtesy a couple of quick YouTube searches

Iguazu Falls/Cataratas del Iguazú/Cataratas do Iguaçu, Argentina/Brazil, South America

Victoria Falls/Mosi-oa-Tunya, Zambia/Zimbabwe, southern Africa

Nothing inspires, and inspires rivalry, like a good big thundering waterfall. A few months back, inspired by travelling friends, I began researching a catarract I knew about but had never visited, Iguazu Falls in South America. What I found was that when it comes to a giant waterfall, people want to know just how giant, and speciffically whether it's gianter than any other waterfall (which is a more difficult question than you might think, given the multi-dimensionality of waterfalls: height, width, flow at a given moment—imagine if Mt. Everest's prestige point for climbers was not that it's the tallest, but by some complicated, debatable formula the biggest. Oh the arguments we'd have!).

In the comparisons I found, Niagra Falls usually gets brought in the picture, especially in the older articles and guidebooks, but that's usually for the quick dismissal of a known quantity. The real showdown, of course, is invariably with Iguazu's African analogue, the probably-more-famous Victoria Falls. Depending on your point of view, Iguazu is "The Victoria Falls of South America"; and Victoria's the "African Iguazu".

(Back in my days editing travel guides such comparisons alternately amused and annoyed. Any city with canals becomes "The Venice of Wherever". The problem with such comparisons is that you're kind of implying the inferiority of the lesser-known part of the equation. "It ain't Venice, but it's the best we've got!")

And indeed, I was amused and annoyed at the waterfall-showdowns. But then I went looking for old maps and discovered something fascinating and (apparently) forgotten.

The Library of Congress's American Memory site proved, as ever, a great good treasure trove. (though difficult to link from ... I've moved some map images over to the blog; to find out more you can, of course, pop over search by the map name or keyword).

All right, first, let's get oriented with this 1998 CIA map. The Falls aren't labelled, but they're right next to the Triple Frontier between Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentina, where the Rio Iguazú flows due west into the Rio Paraná:

South America (1998)

Things were proceeding much as expected ... the falls were unlabeled, or marked with the name of the Brazilian border town, Foz do Iguaçu. But then I clicked onward to an 1873 map, from an atlas published by Charles Black and Co., Edinburgh, Scotland, and saw, where the Rio Iguazú flows into the mighty Paraná, an unfamiliar—or rather, too familiar—name:

Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay & Guayana. (1873)

Instead of Salto del Iguazú, it was labelled Salto Victoria—literally, Victoria Falls! Was this some kind of Rule Britannia-style joke by the Scottish geographers? Some kind of continental clerical blunder? Or a cruel brief renaming of the falls in honor of Brazil and Argentina's then-recent evisceration of Paraguay during the War of the Triple Alliance?

Over the next few days I dug up more info on the surprising references to Iguazu Falls as Salto Victoria. I did find one other old map (Brazilian, 1908) with it labelled as Salto Victoria. All the others either just marked it as "salto" or didn't show anything beyond the intersection of the Iguazú and Paraná rivers.

Mappa geral da Republica dos Estados Unidos do Brasil (1908)

Paraguariæ Provinciæ soc. jesu cum adiacentibg. novissima descriptio ... (1732)

Having gotten through the maps, I started in on text searches—all but the first are from the ever-expanding 19th century universe that is Google Books. Thus, I guess, the 19th century all caps headlines. Anyway.

Here's a story of the Falls' naming from an Argentinian tour operator:

A tourist venue par excellence, it was first glimpsed in the year 1542, when Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca was crossing from the Atlantic Ocean to Asunción in Paraguay. The conquistador, amazed at the sight of the falls, christened them as "Saint Mary's Falls", a name which over time was replaced by its primitive Guaraní name: "Iguazu" (I: water; Guazú: great), i.e. "great waters".

Iguazu. At that time the region was inhabited by natives of the Mbyá-Guaraní tribe, who, around 1609, began to live within the evangelizing influence of the Jesuit fathers, who set up an experiment unique to Latin America: the establishment of a system of "reductions", that at its height included 30 towns scattered throughout the regions of the Tapé and the Guayrá (currently the south of Brazil and Paraguay), all the Argentine province of Misiones, and part of the north of Corrientes.

Political and economic differences with the throne of Spain led to the expulsion of the Jesuits from the region in 1768. The zone of the waterfalls passed into oblivion from then on until August 1901, when the explorer Jordan Hummell organized the first tourist excursion to the area. One of those travelers was Victoria Aguirre, who, when this excursion had to turn back for lack of proper roads, donated a large sum of money to open a land-route between Puerto Iguazu and the waterfalls. This date marks the beginning of tourist trips to Iguazu, and has been claimed by the community as its foundation day, in homage to Victoria Aguirre, who then became a kind of protector, a driving force for the growth of tourism and of the population.

THE CONQUISTADOR CABEZA DE VACA DISCOVERS THE FALLS —BUT DOESN'T MENTION WHAT (IF ANYTHING) HE CALLED THEM

"The current of the Yguazú was so strong that the canoes were carried furiously down the river, for near this spot there is a considerable fall, and the noise made by the water leaping down some height rocks into a chasm may be heard a great distance off, and the spray rises two spears high and more above the fall. It was necessary, therefore, to take the canoes out of the water and carry them by hand past the cataract for half a league with great labor. Having left that bad passage behind, they launched their canoes and continued their voyage down to the confluence of this river with the Paraná."—Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, Commentaries, translated in The Conquest of the River Plate (1535-1555) (New York: 1891)

Also, this French chronology mentions Cabeza de Vaca's discovery of the falls "later called victoria". And an 1892 New York Geographical Survey account mentions a "magnificent but little-known cataract called 'Salto Victoria' or the 'Hundred Cataracts'. These falls occur on the Iguazú River, a branch of the Paraná, about twenty miles from its mouth." After describing the trouble one must take to get upriver to view the falls, we get the usual extreme traveller's payoff:

The numerous tributary streams pouring over these cliffs, together with the principal cataracts form such a bewildering mass of falls, that one is utterly overwhelmed with the sublimity of the scene; and probably for combined beauty and grandeur of scenery, for wildness and variety of aspect, the "Hundred Cataracts" stand unsurpassed.

BUT NOW: PROOF THAT BRITISH AND BRAZILIAN REFERENCES TO THE SOUTH AMERICAN FALLS AS "VICTORIA" PREDATE LIVINGSTONE'S ARRIVAL AT THE AFRICAN FALLS

"The Rio Iguassú, or Curitiba, runs east and west for about 300 miles: it is navigable in the middle of its course, but before it reaches the Rio Paraná it forms a succession of water-falls, of which one, about 10 miles from its moth, is said to be 120 feet in perpendicular height; this fall is called Salto de Victoria. The country on both sides of the lower parts of its course is thickly clothed with high timber-trees."—America and the West Indies Geographically Described (London: 1845)

"Victoria. Cachoeira do rio Iguaçu, 15 legoas pouco mais or menos, acima de sua confluencia com o rio Paraná. Entre a cachoeira Cayacanga d'este rio, e nas terras e matas adjacentes vivem diversas nações d'Indios que estão ainda por se civilizar."

"Victoria. Waterfall of the river Iguaçu, 15 leagues, more or less, above its confluence with the river Paraná. The Cayacanga waterfall of this river enters[?], and in adjacent lands and bushes diverse nations of Indians live that are still uncivilized."

MEANWHILE, AT THE OTHER VICTORIA FALLS

David Livingstone reached and subsequently named the African Victoria Falls ten years later, on Nov. 17, 1855. Here's his account.

LATER ON, AN ARGENTINEAN DICTIONARY GIVES A POSSIBLE ETYMOLOGY FOR SALTO DE VICTORIA

"Se le dió el nombre Victoria (y no de la Victoria) porque los primeros españoles, venciendo mil dificultades, salvaron ese salto."Later in the same dictionary entry came this bit of comparison:

"It is called Victory (and not the Victory) because the first Spaniards, overcoming a thousand difficulties, made it past the falls."—"Victoria—Cataracata—Llamado Salto—Missiones—En el Rio Iguazú", in Diccionario geográfico estadístico nacional argentino, entry: (Buenos Aires: 1885)

Nostros presenciábamos seguramente un espectáculo de primer órden, que sobrepasa a las decantadas maravillas de los Saltos de Niágara, Nyanja y otros, y estamos seguros que llamará la atencion de todo el mundo civilizado.I've had trouble figuring out whether Nyanja refers to the African Victoria Falls (that would make the most sense, given the comparison). Nyanja is one of the main languages of Zambia and the region around the Falls, and seems to be a more general term for lake, and one specificly applied to Lake Nyasa/Malawi, which is quite a bit further east. Livingstone records the pre-colonial name of Victoria Falls (and today the official title) Mosi-Oa-Tunya, which means "the smoke that thunders" in the Kololo/Lozi language. Other local languages give the falls names with that same meaning, e.g. Shingu wa mutitima (Bakota/Tokalaya) and aManza Thunqayo (Matabele).

We are thus surely witness a spectacle of the first order, which surpasses the marvels of the Falls of Niagra, Nyanja, and others, and we are sure that they will seize the attention of all the civilized world.

AND NOW, SUMMING UP

What I found most surprising about this episode was not that there was a little-known former name for a famous geographical feature, but that it seemed to be so widely known 100 years ago, and yet no contemporary sources (at least web-searchable—that's a big caveat) seemed to mention the fascinating fact that the bigness debate between Victoria Falls and Iguazú Falls is, in fact, a case of even closer parallels. Surely there are historians of Latin America out there who know about Salto Victoria, Saint Mary's Falls, the Hundred Cataracts, and the Falls or Foz or Salto or Corrientes of the mighty Iguazú, Yguassu, Iguaçu.

At the end of the day, I think comparisons between waterfalls and cities with canals and so forth are fine and useful, as far as they go. I think having, and learning, multiple names for things is wonderful. The more the merrier. It's always fun trying to figure out the "original" name of some great site, but also to realize that quite often there's no one traceable original (just as, so often, there's no one traceable "discoverer", especially once you set the big-name explorers in their proper place).

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

7/03/2007

0

comments

![]()

Labels: africa, argentina, brazil, english, exploration, geography, history, indigenous, malawi, paraguay, placenames, portuguese, south america, spanish, sublime, waterfalls, zambia, zimbabwe