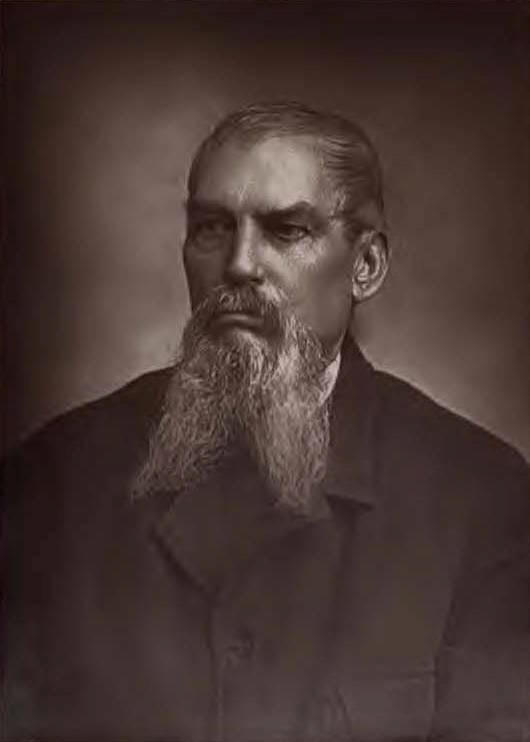

This week I finished reading Richard F. Burton's Letters from the Battle-Fields of Paraguay, a narrative of travels the famed Victorian explorer-linguist-diplomat undertook during the closing phases of the disastrous (but attractively-named) War of the Triple Alliance, at the turn of the 1870s. Burton's journey was a sort of offshoot as his tenure as a British consul to the Brazilian Empire, and it's clear that, as far as the war went, his sympathies were with the Brazilians (and to a lesser extent their Argentine and Uruguayan allies). Like most old travel writing, it refuses to resonate for long with modern interests (hence: his true-to-title detailed descriptions of mouldering earthworks, artillery positions and peculiarities, written for an age familiar, after the Napoleonic, Crimean and US Civil wars, with the terminology), and ruffle modern feathers (of course he says all sorts of insensitive, scornful things about the people and cultures he encounters—though with Burton, it's scorn backed up, right or wrong, by brilliance and deep and broad linguistic and cultural knowledge: twenty-odd languages mastered; as many countries and colonies on four continents explored).

This week I finished reading Richard F. Burton's Letters from the Battle-Fields of Paraguay, a narrative of travels the famed Victorian explorer-linguist-diplomat undertook during the closing phases of the disastrous (but attractively-named) War of the Triple Alliance, at the turn of the 1870s. Burton's journey was a sort of offshoot as his tenure as a British consul to the Brazilian Empire, and it's clear that, as far as the war went, his sympathies were with the Brazilians (and to a lesser extent their Argentine and Uruguayan allies). Like most old travel writing, it refuses to resonate for long with modern interests (hence: his true-to-title detailed descriptions of mouldering earthworks, artillery positions and peculiarities, written for an age familiar, after the Napoleonic, Crimean and US Civil wars, with the terminology), and ruffle modern feathers (of course he says all sorts of insensitive, scornful things about the people and cultures he encounters—though with Burton, it's scorn backed up, right or wrong, by brilliance and deep and broad linguistic and cultural knowledge: twenty-odd languages mastered; as many countries and colonies on four continents explored).

Still there's much of interest to quote—mostly with a wincing sort of humor. So I'll get on with it, in order of appearence in the book. First, some proof of Burton's general view that Paraguay had it (i.e. near-total destruction at the hands of the Alliance) heartily coming:

The war in Paraguay, impartially viewed, is no less than the doom of a race which is to be relieved from a self- chosen tyranny by becoming chair a canon by the process of annihilation. It is the Nemesis of Faith; the death-throe of a policy bequeathed by Jesuitism to South America; it shows the flood of Time surging over a relic of old world semi-barbarism, a palaeozoic humanity. Nor is the semi-barbaric race itself without an especial interest of its own. The Guarani family appears to have had its especial habitat in Paraguay, and thence to have extended its dialects, from the Rio de la Plata to the roots of. the Andes, and even to the peoples of the Antilles. The language is now being killed out at the heart, the limbs are being slowly but surely lopped off, and another century will witness its extirpation. [link]Luckily the nation, civilization, and language did survive (see an earlier post for a bit more on that). For one so scornful, though, Burton did spend three years "mastering" Tupi-Guaraní, and throughout endeavors to search out proper etymologies for placenames (commenting that if he doesn't, he's sure they'll soon be lost).

And first of the word "Paraguay," which must not be pronounced "Paragay." The Guarani languages, like the Turkish and other so-called "Oriental" tongues, have little accent, and that little generally influences the last syllable : a native would articulate the name Pa-ra-gua-y. [link]Language done, he moves on to diet. Paraguayans, from what I hear, now eat tons of meat, just like their Southern Cone neighbors.

The Paraguayan is eminently a vegetarian, for beef is rare within this oxless land, and the Republic is no longer, as described by Dobrizhoffer, the "devouring grave as well as the seminary of cattle." He sickens under a meat diet; hence, to some extent, the terrible losses of the army in the field. Moreover, he holds with the Guacho [sic, Gaucho], that " Carnero no es came"—mutton is not meat. Living to him is cheap. [link]Burton is deeply anti-Jesuital (I wonder what he'd made of the movie The Mission? "Popish propaganda!") and blames the Paraguayans' so-called infiriority on the centuries-past influence of the priests.

A curious report, alluded to at the time by most Jesuitical and anti-Jesuit writers, and ill-temperedly noticed by Southey, spread far and wide—namely, that the Fathers were compelled to arouse their flocks somewhat before the working hours, and to insist upon their not preferring Morpheus to Venus, and thus neglecting the duty of begetting souls to be saved. I have found the tradition still lingering amongst the modern Paraguayans. [link]For all the scorn and asides, Burton does write beautifully and precisely, especially—to modern eyes—in numerous sections describing the natural vistas of the wide and mighty Paraná river. I've read quite a bit about Argentina but this enriched the picture like nothing else:

The channel winds wonderfully, to the east, to the south, and to the north-west. Rival channels abound, and we often see far beyond the monte-bush, to our right and left, ships' sails passing up over land like the sailing waggons of the Seres. When the waters are out, temporary cross-cuts, as on the great Rio de Sao Francisco, enable boats to cruise across country. The riverine edges wax higher as we advance, and whilst one side grows grass the other becomes tree-clad; higher up, this formation will assume larger and more distinct proportions. From this lower bed the larger animals, so common up stream, have of late been frightened away ; the fish to breed in the tributaries and the less disturbed parts ; and little life save aerial remains. At rare times a bullet head protruded from the water and at once withdrawn denotes the "Nutria" indifferently described as an otter, a seal, or a sea-wolf. The shag, plotus, or diwr, is of two kinds, one dingy brown, the other black with white-tipped wings and a plume that commends itself to what wears bonnets. They gaze at us with extended necks and " bob" down stream, in remarkable contrast with the hunchbacked, motionless Mirasol or white crane, standing one-legged and meditative on the bank, and with the Socoboi, the large ash-coloured heron, roaring like a bull because we dare to disturb him. [link]But, soon enough, back to scorn. Burton finishes with the boring paltry fortifications and arrives in Asuncion, the evacuated, occupied Paraguayan capital (the dictator Lopez having taken his soldiers into the jungle to fight to the end). That final sentence presages great bitter 20th century travel writers like Graham Greene, V.S. Naipaul and Paul Theroux:

A few paces beyond the cathedral lead us to the Hotel de la Minute. The house once belonged to a Paraguayan of importance. It fronts a new theatre of ambitious size, said to be built upon the model of " La Scala/' and fitted for 1000 spectators. Its flanks are one hundred yards long; in fact, it occupies a whole " cuadra."* The brick walls that back the three tiers of boxes are four feet thick; they must be fearless of fire, and, after the usual theatres of South America, they suggest the Coliseum. The building was unfinished, and of course a dead mule occupied the inside. [link]Finally he gets round to the weather:

It is popularly said here, as in the Brazil, that summer and winter meet in one day, and that Paraguay combines the four seasons in twenty-four hours. Between midnight and 6 A.M., it is spring; summer then extends to noon: the third quarter is autumn; and from 6 P.M. to midnight it is winter. [link]One closing note: Burton himself enjoys poking fun at the various names given to Paraguay by analogy-hungry writers of his era: "The China of South America" (both closed contries! both grow 'tea'!), "The Sebastopol of the South" (just like the Crimea! in that there was a war!), and—my favorite—"Prester John's Southern Kingdom" (a lost tribe of primitive, wealthy Christians!). And, clearly, so do I.

No comments:

Post a Comment