Last fall I set myself the goal to draw a quick sketch of a person from each and every of the 244 Wikipedia-sanctioned countries in the world, in alphabetical order and alternating between men, women, boys, and girls (hence the name of the project). I started with "Abkhazia Man" in October, 2006 and finished "Zimbabwe Girl" in August, 2007. The source images were found using flickr or Google searches. All the photos were drawn with a Bic ballpoint pen in a nice black notebook I had left over from my dot-com days. Here's an embedded flickr slideshow:

The next order of business, of course, will be to figure out how to present these images in map form.

Till then, some notes on the project: throughout, I was aware of the problematic notion of selecting a de facto "representative" portrait for every country—and the equally-problematic notion of pretending that I wasn't. This problem is obvious for widely multiracial countries like the USA or Malaysia (who gets to be "the" American face?), but perhaps more insidious for presumably "less-diverse" countries like Sweden or Zambia, where choices between "traditional" or "modern" faces might bear their cultural baggage more subtly. So part of my way-out was to leave it up to the search results, picking the first striking and sketchable-by-me face that came up in the returns. But even the fact that I simply tried to dismiss people who seemed to be obvious tourists in favor of those who looked to me like locals, undermines that algorithm.

Well, whatever. My goal for the project was to give myself the chance to explore and rejoice in the variety of the world's faces, and I think I achieved at least a bit of that in my compilation. As for the artwork itself: it is nearly universally safe to assume that my sketches don't do the source images, let alone the people behind them, justice. Usually I was pleased if my portraits looked like a plausible person, if not the one I was trying to draw.

In general I think the younger women and girls bore the worst of my artistic lapses: an ill-plotted jawline on a guy could usually be turned into a five-o'clock shadow, but finer features proved less forgiving of my misdrawn lines. And I don't think I came near depicting the wonderful variety of my subjects' skin tones (dulled though they were by photography). Often as not, folks I was trying to draw darker just got scruffier.

The project has certainly been much more of an exercise than a finished artwork—hence the occasional experiments with widely varying techniques of line and shade. I'd hoped, from A to Z, that I'd get better and better at drawing ballpoint portraits. In the end, though, I think I mainly got faster.

Tuesday, September 25, 2007

Man/Woman/Boy/Girl

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

9/25/2007

1 comments

![]()

Labels: art, boy, drawing, faces, geography, girl, illustration, man woman, ongoing projects, sketches

Saturday, September 15, 2007

Very Early Cinema: Moon Guns and Rubber Heads

This week I watched a very interesting French documentary Le fantôme d'Henri Langlois about the manic-obsessive-brilliant-wonderful film preservationist who founded the Cinémathéque Française. Along the way, he mentioned the two contrasting foundational figures of French cinema, the Lumière Brothers, and George Méliès. Here's a sample of the former:

The Lumière clips they included were definitely fascinating—how could documentary footage of people walking around in 1895 not be fascinating? but the Meiloc ones really piqued my interest (as they did Langlois'—he used to pull out the old, flammable prints to show them as a special treat to the Cinematique's imployees). I'd heard him mentioned in Michael Silverblatt's interview with Brian Selznik, whose illustrated novel The Invention of Hugo Cabret is full of magical Méliès referencces and tips-of-the-hat. The thing that stuck with me there was the comment that, although Méliès discovered and pioneered all of these amazing and surreal special effects, he never discovered (or at least used) that most basic of effects: moving the camera. All of his shots are framed more or less like a theater stage—or, better said, the stage in a magic show.

Here are two Meiloc films from YouTube, L'homme a la tête en caoutchoc ("The man with the rubber head", 1901) which is a more basic magic-show setup, and the delightfully surreal (and famous-in-places) Le voyage dans la lune ("A Trip to the Moon", 1902), which crams near-infinite motion into that non-moving camera.

Wednesday, September 12, 2007

The Ruffian Bombardment

A few of my friends are in Lebanon for pre-wedding festivities this week; in honor of that I found this 1799 travel narrative (Travels in Africa, Egypt, and Syria, from the Year 1792 to 1798 by William George Browne) which has that distinct eighteenth-century advantage, namely that the lower-case s's are typeset almost the same as f's, giving the whole thing a very funny lisping look, and not a few fun outright misreadings (like that key Syrian export, filk).

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

9/12/2007

0

comments

![]()

Labels: beirut, lebanon, orthography, travel, typography

Sunday, September 9, 2007

And There Was Much Rejoicing!

Google Books now allows for easy posting of old, good book snippets. This removes about eight steps from my process. Let's celebrate with a (presumably hand-colored) plate from an Oxford library copy of Foreign Butterflies by James Duncan (London: 1858):"

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

9/09/2007

0

comments

![]()

Monday, September 3, 2007

More Songs about Trains and Buildings: A World Music Fable

Prelude: Nine years ago when I was editing travel guides, it was a matter of pride for the musically-inclined editors to blast the office with guidebook-appropriate (or hilariously-innappropriate) music. For me, of course, that was arranged with a perpetual connection to a Bollywood-themed internet radio station. Over in the "domestic" room, the editors played Frank Zappa, Jonathan Richman, and, when a great laugh was needed, the following song, by French pop master Serge Gainsbourg:

[N.B. This embed, and for that matter the others, doesn't seem to work ... you can get the same effect by going to www.deezer.com and searching for "Serge New York". I'll work on the odeo players soon, I hope]

Robin D.G. Kelley: Drum Wars [1hr lecture]

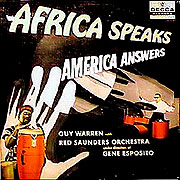

In this particular lecture he was talking about the specific mid-twentieth-century debate over who was and wasn't an "authentic" African drummer during the early cross pollinations between American jazz and music from contemporary Africa (the music itself, of course, having elements traditional and contemporary). Kelley's lecture is a lot about Guy Warren, who came from Ghana to the states in the early(?) 1950s with the goal of introducing the talking drum to American jazz. His first records wound up coming out around the same time, more or less, that a few African-American jazz drummers (Art Blakey, and later I think Max Roach) were starting to use explicitly African titles and themes in their records. Basically Warren thought Blakey et al's music wasn't African at all, and was for that matter completely uninteresting.

In this particular lecture he was talking about the specific mid-twentieth-century debate over who was and wasn't an "authentic" African drummer during the early cross pollinations between American jazz and music from contemporary Africa (the music itself, of course, having elements traditional and contemporary). Kelley's lecture is a lot about Guy Warren, who came from Ghana to the states in the early(?) 1950s with the goal of introducing the talking drum to American jazz. His first records wound up coming out around the same time, more or less, that a few African-American jazz drummers (Art Blakey, and later I think Max Roach) were starting to use explicitly African titles and themes in their records. Basically Warren thought Blakey et al's music wasn't African at all, and was for that matter completely uninteresting. Side note no. 1: Guy Warren's first album, "Africa Speaks, America Answers" was recorded with the Chicago band he'd been playing with -- a band, which was, with the exception of Warren and an African-American drummer, composed entirely of Jews and Italians (who nonetheless did all right with the call and response stuff). Prof. Kelley also noted, as something of an aside, that although several influential African-American jazz musicians were drawn particularly to what they saw as the authentic African spirituality of Warren's music, Warren himself was neither Muslim nor Christian nor Animist but in fact a practicing Buddhist. Anyway, Kelley says his music was, perhaps not so surprisingly, ambitious and drew on a ton of different traditions: African, Jazz, classical, etc. This probably made him less than an ideal candidate for the role of "authentic African drummer".

Side note no. 1: Guy Warren's first album, "Africa Speaks, America Answers" was recorded with the Chicago band he'd been playing with -- a band, which was, with the exception of Warren and an African-American drummer, composed entirely of Jews and Italians (who nonetheless did all right with the call and response stuff). Prof. Kelley also noted, as something of an aside, that although several influential African-American jazz musicians were drawn particularly to what they saw as the authentic African spirituality of Warren's music, Warren himself was neither Muslim nor Christian nor Animist but in fact a practicing Buddhist. Anyway, Kelley says his music was, perhaps not so surprisingly, ambitious and drew on a ton of different traditions: African, Jazz, classical, etc. This probably made him less than an ideal candidate for the role of "authentic African drummer".Enter Babatunde Olatunji ... who came to the U.S. from Nigeria on a Rotary scholarship and attended Morehouse College and then NYU grad school, studying political science. To make extra money, he started playing music with an ensemble he'd put together — traditional West African stuff and original compositions, though Kelley notes that a lot of his training as a percussionist had apparently come from African American musicians he'd known since coming to the States.

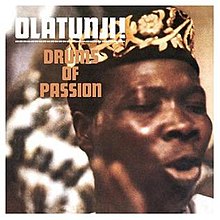

Anyway, Olatunji was playing at Radio City and got "discovered" by a Columbia record exec who signed him and, a year or two later, got him into CBS studios in New York to record "Drums of Passion" — which not only went on to vastly outsell anything by Guy Warren or, I think, any of the other Africanist projects by American jazz musicians, and in fact has never gone out of print, and now gets cited, on various promo-type sites, as being possibly first real (successful) "world music" album, the first real studio-recorded album of real African music, etc. etc. etc.

Anyway, Olatunji was playing at Radio City and got "discovered" by a Columbia record exec who signed him and, a year or two later, got him into CBS studios in New York to record "Drums of Passion" — which not only went on to vastly outsell anything by Guy Warren or, I think, any of the other Africanist projects by American jazz musicians, and in fact has never gone out of print, and now gets cited, on various promo-type sites, as being possibly first real (successful) "world music" album, the first real studio-recorded album of real African music, etc. etc. etc.Whether or not Olatunji was better qualified than Guy Warren to be known as the introducer, at least he turned his popularity into a long and very legitimate career both in the African American, jazz, and world music communities. A few years before he died in the 1990s he did some sort of collaboration with one of the Grateful Dead, though which one I cannot say.

Fascinating story, I thought (and hopefully you think). So I hopped on over to iTunes to see just what the original authentic drummer sounded like. I clicked on the first track of "Drums of Passion" and ... well, something seemed awfully familiar.

Just what was going on here? Who copying who? A few searches turned up lyrics and the story of the song in question—

Akiwowo (Chant to the Trainman)

This is the song about the legendary conductor when railroud trains were first introduced in Nigeria over five decades ago. Millions still remember Akiwowo, who always made sure that his passengers, mostly men and woman returning from their farms with their products balanced on their heads,never missed the train, as well as his warm welcom, broad smile and humor. Akiwowo, now in his eighties,lives happily in the village of Pa-Pa Lanto full of sweet unforgettable memories of his service to his people and country.

Akiwowo Oloko lle

lowo Gbe Mi Dele

Ile Baba Mi

Akiwowo conductor of the train

Please take me home

To my fathers house

As for how exactly "Akiwowo" became "New York USA" let us turn to the following computranslation from Serge Gainsbourg's French record company:

Serge enters in studio from the 5 to October 16, 1964, withIt seems worth noting that whereas "New York USA" was presumably adapted/recorded in France, "Akiwowo" was recorded (and quite likely written) in New York. So without too much difficulty we might imagine Olatunji listening to the clatter of subway or el trains and thinking wistfully back to the famed Nigerian railway conductor. (Incidentally, the click-click-clack percussion makes perfect sense with the original song's rail theme).

Goraguer, for a second 30 cm, "Gainsbourg Percussions". Via Guy

Béart, it impregnates disc "Drums of Passion" of the Native of Niger

Babatunde Olatunji.

For "New York the USA", Serge is inspired — rate/rhythm, arrangements,

melody, technical question and answer between the singer and choruses

— by "Akiwoko (Song To The Trainman)". For "Over there it is natural",

of a counterpoint of Myriam Makeba.

Many years later, when to the USA a disc leaves Serge containing "New

York the USA", Olatunji brought in Gainsbourg a lawsuit for

plagiarism.

[French original]

But of course we are left to ponder what exactly led Serge to impregnate disc "Drums of Passion", and why concerning New York, and for that matter what became of that lawsuit for plagiarism brought in him by the first original real and authentic African drummer in USA.

Postlude: More media!

Here's a much-older Babamayo Olatunji performing a Liberian rhythm:

... and here's, from France's Institut National de l'Audiovisuel, a prehistoric music video of Serge Gainsbourg's "New York USA" — the song begins after a 1min. introduction by the French chanteuse Barbara:

... and — because I could —here's a map of all the buildings Gainsbourg sings about (scroll down for the Bank of Manhattan at the island's tip):

View Larger Map

Sunday, September 2, 2007

Sabbath Poem: The Lantern Out of Doors

"The Lantern Out of Doors" by Gerard Manley Hopkins.

Posted by

Nate Barksdale

at

9/02/2007

0

comments

![]()

Labels: audio, gerard manley hopkins, ireland, poetry, sabbath poems